For me 2011 was the year of LEDs. I started writing a book about how photographers and videographers use LEDs as main light sources in late 2010 but the bulk of the writing and shooting for the book was done in 2011. And I learned a great deal not just about LEDs but about how our choices of tools tend to shape our vision as artists. For example, it's easy to shoot without blur if you use flash, and it's easy to shoot at smaller apertures when you use bigger studio flashes but there's always a trade off. Every stop smaller means more and more is in focus and that might not be the effect you want if you really stop to think about it.

I learned that it's fun to work at the edge. A lot of lenses fall apart when you get close to wide open and a lot of us aren't as great at focusing as we think we are. Neither are our cameras. DSLR's are fast but the trade off, at least at the widest apertures, is accuracy. Shooting with continuous lights that aren't as powerful as tungsten lights means having to pay more attention to technique. Depth of field is a fickle ally at f2...

I learned that writing a book about a subject that is just becoming popular is harder than writing a book about something you've been practicing for 20+ years. (Go figure...). To the best of my knowledge my LED book will be the first book dedicated to showing photographers what's out there and how (and why) to use it. This means that you can't really research much on the web besides product availability and manufacturer hyperbole. You have to actually buy the stuff and play with it and use it until you get the hang of it. And then you have to translate what you learned. I'm sure, in a year, there will be dozens and dozens of books that deal with the same subject and I'm equally certain that most of them will use the entrails of mine to make a new product. Happens all the time in the book business. One only has to look at all the "Small flash on location" books that have hit the market in the last three years to see that.

Writing a book like this is harder than it looks. You have to pioneer some stuff. You have to go out exploring in other fields like the video industry and interior design but, toughest of all, you have to sit down and write. And every time you get the thoughts marshalled just right someone comes out with something new or you realize that you need to create a series of images to show what you're talking about. And for me that generally means finding a model, setting up both the shot and the behind the scenes shot and then creating captions for the photos that are short enough to fit and long enough to get the ideas across.

Once you've written and re-written the manuscript and selected and corrected the 150 or so images you send the whole package off to your editor and wait for their input. Invariably I talk about something that really requires an illustration and the editor is quick to point out the gap. Which means I have to go back to the project and shoot again. The LED book weighed in at about 45,000 words and has been edited down by at least 20% (thank goodness). You make your final corrections, have Belinda proofread it again, send it back and cross your fingers. But it doesn't stop there because every book is really your baby and if you want it to do well you have to play a major part in the marketing. That means getting it in front of people, cajoling good reviews for the all important Amazon.com page and also getting your local camera store to push the book. I'll do book signings anywhere in Texas. Really.

But there's a downside to all this. In fact, there are two. The first is that authors don't get a paycheck, they get royalties. But the royalties don't come in the mailbox until the book is written, photographed and sells. The royalties follow the initial sales by about six months. No sales mean no royalties which means you basically spent half a year of your life working hard on something with very little return. When I believe in what I'm writing that's a risk I'm willing to take because, to a certain extent (a large extent) whether or not the book does well is in my control. I can try to concept better, write better and make better illustrations. I can decide to work harder on marketing the book(s).

The year in which you actually do all the writing and shooting is grueling because, since there's no income from the project yet, you have to keep working at your "day job" and for me that means being available to clients at the drop of a hat to do photographs. And it must be Pressfield's law that the more in the groove and motivated you are to finish your book project the more the clients want and need you. When you hit the last lap of book production is when you get the high production, out of town job that has the world's tightest deadline. And that deadline is usually the day before the book is due.

I remember when I wrote my first book. I'd never done a book project before and I was afraid that the publisher would take a look at my stuff and declare it crap and cancel my contract. I worked and worked on the book and ten days before my deadline I got booked on an out of town assignment for eight days. Lots of details and lots of travel. I would shoot all day, travel in the evenings and try to polish my book late into the night. When I got back home I was trying to do the final lighting diagrams on my computer and I started seeing dark spots in my peripheral vision. Then I couldn't focus on the screen correctly and my heart was racing. I stumbled into the house and asked Belinda to drive me to the hospital. I was certain I was having a stroke (I'm an ace hypochondriac...) and we rushed to the emergency room.

The diagnosis? Acute panic attack. The short term cure? Half a milligram of Xanax. The book got done and went out on time via Fed Ex. And I waited for feedback. On the edge of my seat. And.....nothing. I was certain the publisher was shaking his head and moaning. Finally, a week or two later I called. They loved it. And the book was successful. But the birthing process, for me, was incredibly painful. And it's nearly as bad each time.

But here's the thing that sucks about writing a book, or putting photos on the web, or basically doing any sort of time intensive project like a movie or a book: the minute is hits the book stores, or Amazon or, in the case of movies, a DVD being offered for sale it's stolen and copied and pirated everywhere. I can go to a dozen bit torrent sites right now and download stolen or pirated copies of all four of my current books in English, Polish, Italian and Chinese. Someone will recommend one of my books on a forum and actually post a link to a bit torrent site where they can get it "for free." Pisses me off. But how many days of your life can you commit to doing "take down" orders/requests/submissions?

I hope the LED book hits its audience. But even if it doesn't I enjoyed the process and I enjoyed the "time in the water." And I know it's part of the process of becoming a better writer.

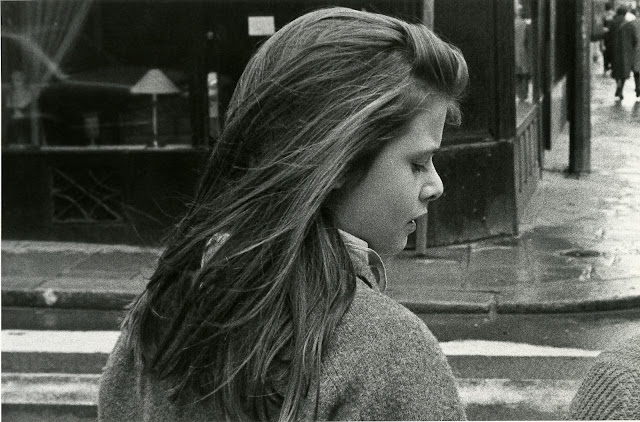

What will 2012 bring? I'm going to go out on a limb and say that this will be the year we re-invent the whole idea of portraiture. From the ground up. New rules. No rules. I'm out to figure out how to make portraits that people look at, gasp, and demand to have at any cost. That's the business goal for me. And I think there might even be a book hiding in there. Sure would give me an excuse to re-invent my whole genre. Yes?

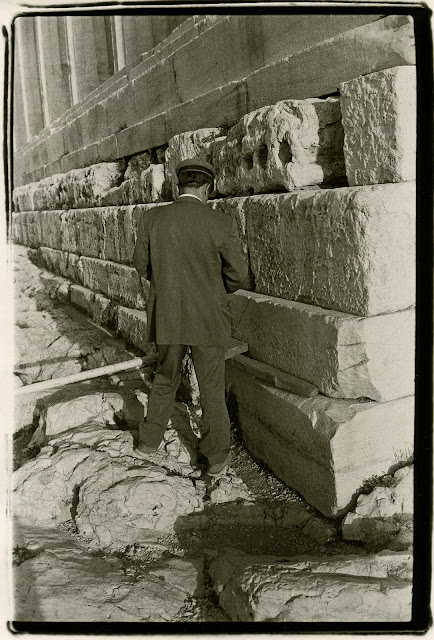

Below. A random LED sampler.

I did want to say that through good times and bad, here on the Visual Science Lab I've had a wonderful time getting to know really smart and engaging people; readers, from all corners of the earth. I've had heart warming e-mails, notes in the real mail and been the recipient of stories that brought tears of happiness to my eyes and a catch to my throat. I know I have a tendency to change course and change my mind but in spite of that I try to write honestly and from the heart.

Some of you think I should be relentlessly positive but that's not a holistic portrait of my humanity. We get pissed off, we see things that shouldn't be, we resist change just for change's sake, and it's folly not to speak out when you feel it. But I do try to layer in as much of a sense of satisfaction and wonder as I feel. And I feel it most days.

Happy New Year. May your pictures make you happy. Screw the critics. See the world through your own lens. That's genuine. Take your photographs instead of copying what everyone else has already done. Be there for your family and friends but make time for yourself. Thank you for being here.