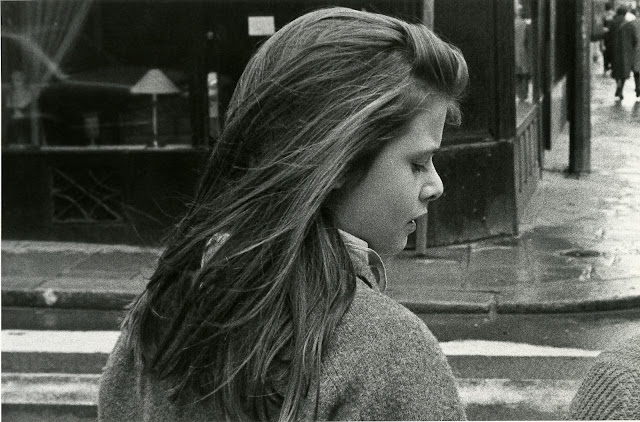

Belinda. Sometime in the last thirty years. Seems like yesterday.

(Originally written in 2004 and modified today)

I was trying to remember all of my initial brushes with photography and piece together when and why the addiction to the process stuck. Christmas in the late 1960's. My unstructured memory of my life before high school would lead me to believe that my family was living at the time outside of Ft. Worth, Texas. Someone in my family got a Polaroid "Big Shot" instant camera and we all took turns using it until the novelty of the fixed focal length and the color quality of the milky, soft, squarish photographs wore off.

My mom and dad were traditional, middle class, single income parents at the time, trying their best to keep everything moving forward while dreading the not too distant cost of paying for three college educations in a row. The cost of unnecessary novelty films seemed as wasteful as tossing quarters from a moving car. We didn't ask for many replacement packs of Polaroid because we were pretty sure that it would come down to a choice between new shoes and film----and our feet were still growing.

I remember stories of my mother going with a Turkish taxi driver to the outskirts of Adana, Turkey to photograph a gypsy tribe with a Kodak Instamatic and color print film---but she rarely pointed this camera at her own family. My next brush with cameras came when I found my parent's older Argus A4 camera, discarded in the garage. It used 127 film. A film size discontinued by Kodak a few years ago. The camera was made of bakelite(tm) plastic and had a finder you composed with but no focusing aids at all. Everything was strictly zone focus. And of course, typical of an inexpensive camera from the 1950's it had no automation or metering whatsoever. But that's why Kodak had pictograms of exposure recommendations packed with every roll of film they sold....

Knowing now my parent's almost pathological resistance to any and all mechanical devices I am amazed at the Kodachrome slides they took of us with this primitive camera back in the very early 1960's.

At any rate, I retrieved it from a box of junk in the garage in our San Antonio home some time in 1971 and revived it. At the time I had no allowance and earned just a little bit of money as a lifeguard at the high school pool. But I bought a roll of black and white film (it was much cheaper to buy and have developed in 1975 than color) and I proceeded to experiment by shooting the only thing that held my interest at the time, my girlfriend, Linda.

Owing to my non-existent technical knowledge and the deterioration of the lens and the body of the camera, the results of my first foray were less than good and I didn't touch a camera again until years later. Sometime around 1974 or 1975 when I had been at school for several years I was working at an audio store, part time. I sold stereo systems (now they are called audio systems). The owner, manager and the other salespeople were avid photography amateurs. One day Herb Ganz flipped open a black Halliburton case that cosseted a family of black Olympus OM-1 camera bodies and lenses, tenderly, in pre-cut cushions of foam. I was hooked.

Herb helped me select and buy my first of many cameras, the Canon Canonet 17 rangefinder. A fixed 40mm 1.7 lens on a sleek and hefty camera that took 35mm film. In the early days that "17" took rolls and rolls of home loader 35mm black and white film. It was the magic of making my first black and white prints in the Ark co-operative darkroom that led me down the path to my photo-addiction and all that it entails.

It will seem odd to the current generations of up and coming photographers that we were able to accomplish so much so well with mechanical units and no computers or instant preview on backlit screens. The moment of my first cognizant love of photography camera when I made a photograph of a cute and adventurous girl friend sitting on some concrete stes in one the neighborhoods just south of campus. She had on her glasses and a cornflower blue Mexican wedding shirt and a baggy pair of short khaki shorts that were quite worn. She sat with her knees up and her legs slightly apart and her shorts billowed out slightly, revealing her white cotton underwear loosely and barely covering her body. I shot a photo. Just one----and I was hooked.

I had reduced her thirsty sexuality and keen sense of playful tease in one inarguably correct image. It would forever conjure up for me the notion of carefree sex and love in the mid-1970's. But with time the photo and the memory of the photo is stronger than any later memory of the same woman. It was at the moment I took the photo that the visual memory imprinted on whichever part of my brain was affected. NOT upon the revelation of the print. Not the final art but the initial conception or discovery of the image. The magic moment for me has always been the realization that there was a scene, a tableau, a moment that had reached a sort of distinct ripeness. I want to freeze "now". And then savor it (the memory) over time.

And here's the funny thing. The photos don't get better or worse. They are always in my mind just the way they were. It's almost as though the matrix that constitutes the right scene and the right time is frozen into an unchanging cube of objective reality. Always my own reality. And, I find, nothing about that sense of reality is universal. I find what I find in each image and it's not mirrored in someone else's viewing. Each person brings his or her own complex reality to the viewing giving the viewer a value commensurate with their own emotional commonalities.

During my years teaching and thru my time in advertising photography existed as a passion, an obsession if you will. I walked thru the streets of cities all over the world discovering the uniqueness of their citizens' existence and the commonality that binds us. As long as I operated in that sphere the enchantment was pretty much complete. And there was a constant and consistent destination for the images I saw, the things I committed to film. The best of the best would become prints and the prints would get shared in shows, both formal and less so.

What I found and find to be most compelling is the way a portrait can capture that thing that led me to find someone interesting, compelling, attractive, delightful and how much I wanted to preserve just that feeling that is a combination of the subject's quick glance, their turn of the head, their sly smile, their earnest eyes.......

This is the way I originally approached taking pictures when I was always the primary audience. As I began to go after paying jobs everything started to shift.

When I photographed primarily for an external audience (an advertising client?) I felt a loosening of emotional control over the ownership of the image. In an image not created for my sole enjoyment I feel a distancing from the work as though it squeaked thru without my complete and complicit approval.

I was struck today with the realization that photography has changed for me in almost every conceivable way. Rather than being a joyous hobby that sucks down every spare dollar, it is a profession that earned me a little over $XX,XXX last month. Instead of spending days in the darkroom coaxing images onto sensitized photographic paper I spend most days tethered to a computer trying to optimize a mish mash (I was going to reflexively write: "mismatch" ) of pixels into beautiful images. The overview challenges are the same: Capture the image and share it on paper. Or, capture the image and share it on the screen. But everything changes from there.

What sucks about all of this? There feels like a disconnection between my thought processes and the computer rendering. Wet photography was more inviting and addictive. It was a learned skill set that was never exactly reproducible. Every print really, REALLY was a unique work of art. Today I spent most of my day processing raw files shot in a UT lab, under existing light, for a technology client. The unsettling aspect was the ease and the degree to which everything in the frame could be corrected. The process seemed so mechanical and cold. Or should I say so binary and cold. And yet, this is the practice of current photography.

The processes all seem compromised. We store images on hard drives and Cd's and DVD's and we're not at all sure if we'll be able to read these media in ten years. The standards, formats and machines will evolove and there is no assurance of backward compatibility. Now we are learning that the CD's and DVD's may not survive the next ten years so that we can even try to using the next successive generation of readers. We can make prints with much more control but they may last only ten or fifteen years before the inks start fading away.....eventually to disregard the work on the paper without a trace. Like an old Ektachrome slide from the 1950's.

Another grievance is the quickness with which everything happens. In the old days clients would show us comps and we would bid. A week later someone would call and tell me I was the successful bidder. Another week would pass as we rounded up props and talent, locations and film. Now clients call and ask for bids with only the most ephemeral description of the project. They want a price immediately and, within the space of a few hours they award the project. They push to shoot immediately with no thought for pre-production (physical) or a thorough thinking through. No, everything seems so transient and thin. Gone are the underpinnings and thoughtful foundations of art. And whether a photographer admits this or not, they are all in it for the art.

So how do I make it work again? How can I be happy doing the work?

I'm thinking these things when I run into John at Chipotle's. We're both ravenous for burritos. Ben and Belinda were there too. We got to talking about how different cultures live and he told a story about a cheese maker in Italy.

The man was 58 years old and all he made was Parmagiano Reggiano cheese. But he made it better every year. And better than everyone else. It always won the top awards in all the food shows and the vitally important cheese competition. Finally, after 20 years the contest officials retired his entry number so that someone else could win. The point was that as a society we don't value mastering and craftsmanship. Only instant gratification. We need to re-value and resell the whole concept of mastery. Maybe that's what gives meaning to our efforts. A non-plastic recording of beauty and sensuality.

But what does this have to do with why I photograph? Because, in spite of my feelings about the commercial marketplace I still pick up my cameras every day and take pictures that delight me....

(added today)

So, I came across the above in one of my journals and it became the basis for a whole train of thought for me today. And at the bottom of the process is still the question, "Why take photographs?"

Looking at all of this some seven years later is interesting. The cultural switch over to digital imaging is more or less complete. The retreat from the high production demands of fine print to the less produced but more immediate display on screens is largely in its last phase and the mantra of the last two years (with my voice occasionally included) is that moving images will conquer the still market. As though it's inevitable and only a matter of time....

And that led me to re-examine my whole premise and my whole interaction and allegiance to all the plastic arts. And here's what I've found (which in no way is original thinking but in fact is the echo of a pervasive counterstream of philosophy of aesthetics about imaging) : I've been doing video for a while and no matter how entrancing I've never had a memory for a scene of video. When I think about a subject my brain conjures up a still image. The moving footage doesn't resonate in the same way. It has power, yes, but no stickiness. In the same way that movies are transient and what we really remember is the emotion and the dialogue but not the stunning shot. (although there are a handful of exceptions). But still images have a singular power to tattoo layers of information right onto some part of the brain. And they stick there and become symbols for ideas, experiences and emotions. And even many years later that stickiness in the brain speaks to the power of the single image.

When we look over the history of the last century or even of last week it's not the documentary footage that we remember because our brain is not good at cataloging so many interwoven frames into a composite for good storage. Our brains crave the single, fully formed and singular image in their cataloging process. Nothing else comes close.

There's lots of grainy motion picture footage from the Viet Nam war but the images we remember are the still images of the cursory execution of a captured officer taken by Eddie Adams. We remember Ut's photo of the girl running down a road burned by napalm. Images from Iraq trump footage from Iraq, in the stores of our memories.

And so it is also with our personal images. We might have film of our fathers and mothers but our memories are stabilized, reinforced and preserved by the still images we covet. And it's more than nostalgia it's brain science. It's the science of memory and vision.

And so, I've come full circle and entrusted my wonder and amazement at life to my still camera. Video is a powerful marketing tool and it works in the "here and now" but still images have a resonance or a repeating "pass along" factor that can't be beat. If you take a photo of an event that is powerful to you its resonance remains undiminished and this is the true power of photography. To be able to evoke memories and emotions and context without even needed to re-see the photograph once you've initially experienced it. And re-experiencing it can be an additive experience as new subsequent learning is leveraged into your subconscious appraisal of the viewing experience.

I long labored under the depressing idea that the art form I had come to love so much was dying. That we were in the process of writing its obituary. Only to rediscover that it has a power that other media can't match and for that reason alone it earns it's place in the hierarchy of visual art. It is the pervasive nowness of video that gives it power. It's the staying power of still images that gives them their pervasive value. That's not going away and neither are we.

In the past seven years we've lived thru so much and so many cultural adaptations have been made as a result of our diminishing economic power and our fear of global events, relentlessly presented. We are all in a funk of post traumatic stress re-order and it colors our perceptions of value and purpose. But one thing I am sure of and that is we photographers will always want to photograph the things we find special so we can make that indelible tattoo on our own brains of the things we never want to forget. And that's why this is such a valuable art. Photography = permanent brain tattoo.